Wind power: your questions answered

Wind power is one of the UK's most abundant sources of renewable energy and we're therefore asked a lot of questions about it. Here we address some of the most frequently asked questions, myths and misconceptions surrounding wind energy, wind turbines and wind farms.

Can wind farms really produce enough power to replace fossil fuels?

The UK government’s British energy security strategy sets ambitions for 50GW of offshore wind power generation – enough energy to power every home in the country – by 2030. However, as wind power can be intermittent, a reliable strategy for phasing out fossil fuels requires a number of different clean energy sources, as well as ways to share and store this energy to ensure there’s always power available when and where it’s needed.

Find out how we can still have clean energy when the wind doesn’t blow and the sun doesn’t shine

Does the amount of energy that wind turbines produce make up for the amount that’s needed to manufacture them?

The average windfarm produces 20-25 times more energy during its operational life than was used to construct and install its turbines. This was the finding of an evidence review published in the journal Renewable Energy, which included data from 119 turbines across 50 sites going back 30 years.

The Institute of Environmental Management and Assessment (IEMA) states that the average wind farm will pay back the energy that was used in its manufacture within 3-5 months of operation.

Do old wind turbine blades end up in landfill, or can they be recycled?

Wind turbines can mostly be recycled at the end of their working life and are increasingly being made from materials that have already been recycled.

The blades are made from different materials, most of which is fibreglass. Fibreglass is not totally recyclable and is usually discarded as waste at landfills or incinerated. However, while many first-generation commercial turbine blades are being treated as waste, not all of them are destined for landfill. There are several innovative ways that their raw materials are being recycled to be used in other building materials or repurposed entirely.

Engineers and scientists have found a way to turn fibreglass into a key component used in the production of cement – an important material used in everyday construction. They’re also finding ways to repurpose turbine blades as structural elements in their entirety; these include bike sheds in Denmark, noise barriers for highways in the US, ‘glamping pods’ across festival sites in Europe, or as parts of civil engineering projects, such as pedestrian footbridges, in Ireland.1

Read more about what happens to old wind turbine blades

What happens when wind farms produce more energy than is needed – does the energy just go to waste?

The amount of wind power being generated depends, of course, on the consistency of the wind. This means that when wind power is at its peak, the amount of electricity being generated could potentially outstrip the amount that’s required by homes and businesses at that particular time.

Fortunately, there are solutions to make sure excess wind energy doesn’t simply go to waste:

1. Storing energy to be used later

Excess electricity can be captured and stored, to be used at a later time when there’s not enough electricity being generated to meet demand. The most popular option for this is battery storage, but there are other methods of storage being developed all the time.

Find out more about renewable energy storage

2. Sharing energy with neighbouring countries

Electricity interconnectors are high-voltage cables that allow excess power to be traded and shared with neighbouring countries. When supply exceeds demand, we can send the excess electricity to another country and vice versa.

Find out more about interconnectors

Is it true that wind farms are paid to switch off on very windy days because they’re producing too much energy?

The work we’re doing to upgrade the electricity grid in England and Wales – known as The Great Grid Upgrade – will help to ensure that any excess energy generated by wind farms can be used to power more homes and businesses with clean energy. So on very windy days we’ll be able to make the most of the large amounts of electricity being generated and wind farms won’t need to be switched off.

There are a number of ways that we can maximise on excess wind energy:

- Improving connections to the grid, which means that more of the electricity from wind power can be transmitted around the country

- Sharing the excess energy with neighbouring countries via interconnectors

- Connecting more energy storage to the network, which can store excess renewable energy for use at a time when it’s needed

Upgrading the UK’s electricity grid to maximise on clean energy

In order for homes and businesses to use cleaner, greener energy, more renewables – such as wind power and solar power – will need to be connected to the electricity grid. To do this, we'll need to upgrade the existing grid, as well as building new infrastructure, to reinforce the network and make sure this clean electricity can be transported from where it’s generated to where it’s needed. The Great Grid Upgrade is the largest overhaul of the grid in generations and will make sure everyone in England and Wales has access to clean, secure energy.

Do turbines need fast wind speeds to generate a good amount of wind power?

It’s not the speed, but the consistency of wind that produces the most wind power. Wind turbines will generally operate between 7mph (11km/h) and 56mph (90km/h). The efficiency is usually maximised at about 18mph (29km/h) and they will reach their maximum output at 27mph (43km/h).

Isn’t coal – a fossil fuel – needed to produce the steel that wind turbines are made from?

For centuries, the steel industry has relied on coal to fuel its manufacturing processes, so this is something that can’t simply be changed overnight. But steel manufacturers around the world are looking at alternative methods of producing steel using cleaner sources of energy, such as green hydrogen or renewable energy sources. There are much lower-carbon ways to make steel already in use today and the technology for zero-carbon steel is already in existence.

Alternative materials are also being explored for building wind turbines; for example, Swedish start-up Modvion has developed a system to build turbine towers using sections of laminated wood. They claim that using timber rather than steel generates 90% less carbon dioxide emissions. Plus, when the turbine comes to the end of its life, the modular segments from the tower can be reused.2

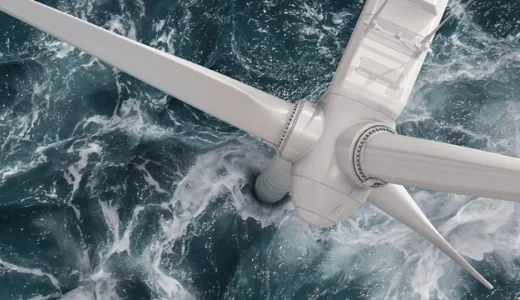

Are offshore wind farms harmful to whales, dolphins and bird species?

Wind farm developers work closely with local environmental groups when consulting on the siting and scale of wind farms. However reports in both the US and UK conclude that currently there is no evidence of wind farms causing harm to wildlife.

NOAA Fisheries, the office within the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration responsible for the management of marine life, say: “There is no scientific evidence that noise resulting from offshore wind site characterisation surveys could potentially cause mortality of whales. There are no known links between recent large whale mortalities and ongoing offshore wind surveys.”3

Regarding whale strandings in the UK, Carbon Brief reports that Carl Donovan, a lecturer at the University of St Andrews Scottish Oceans Institute who has studied the environmental risk of sound exposure in marine mammals, states: “Marine mammals strand for various reasons [that] can be hard to ascertain. An operational windfarm would be low on the list.”

Paul Jepson, CSIP principal grant holder and reader at the Zoological Society of London, also told Carbon Brief: “We don’t have any evidence for windfarms causing cetacean mass/single strandings… That’s not to say that a windfarm can never cause a whale mass stranding – but we just have no evidence of that so far.”4

When it comes to seabirds, a 2023 study that mapped the flightpaths of thousands of birds around wind turbines in the North Sea found that they deliberately avoid wind turbine rotor blades offshore. Most importantly, during two years of monitoring using cameras and radar, not a single bird was recorded colliding with a rotor blade.5

When it’s not windy, how will we have enough clean energy to power the country?

Because electricity generation from natural sources like wind or solar energy can be intermittent, there are a variety of solutions for providing clean energy that doesn’t rely on the sun or wind.

Find out how we're making sure that there’s enough clean energy to meet demand, even when the wind isn't blowing and the sun isn't shining.

What happens when the wind isn't blowing and the sun isn't shining?

Last updated: 1 Mar 2024

The information in this article is intended as a factual explainer and does not necessarily reflect National Grid's strategic direction or current business activities.

Sources

1 Chemical & Engineering News: How can companies recycle wind turbine blades?

2 Wind power: Wooden turbines could make industry more sustainable | New Scientist

3 Frequent Questions—Offshore Wind and Whales | NOAA Fisheries

4 Factcheck: Whale strandings and offshore windfarms - Carbon Brief

5 Unique study: birds avoid wind turbine blades - Vattenfall