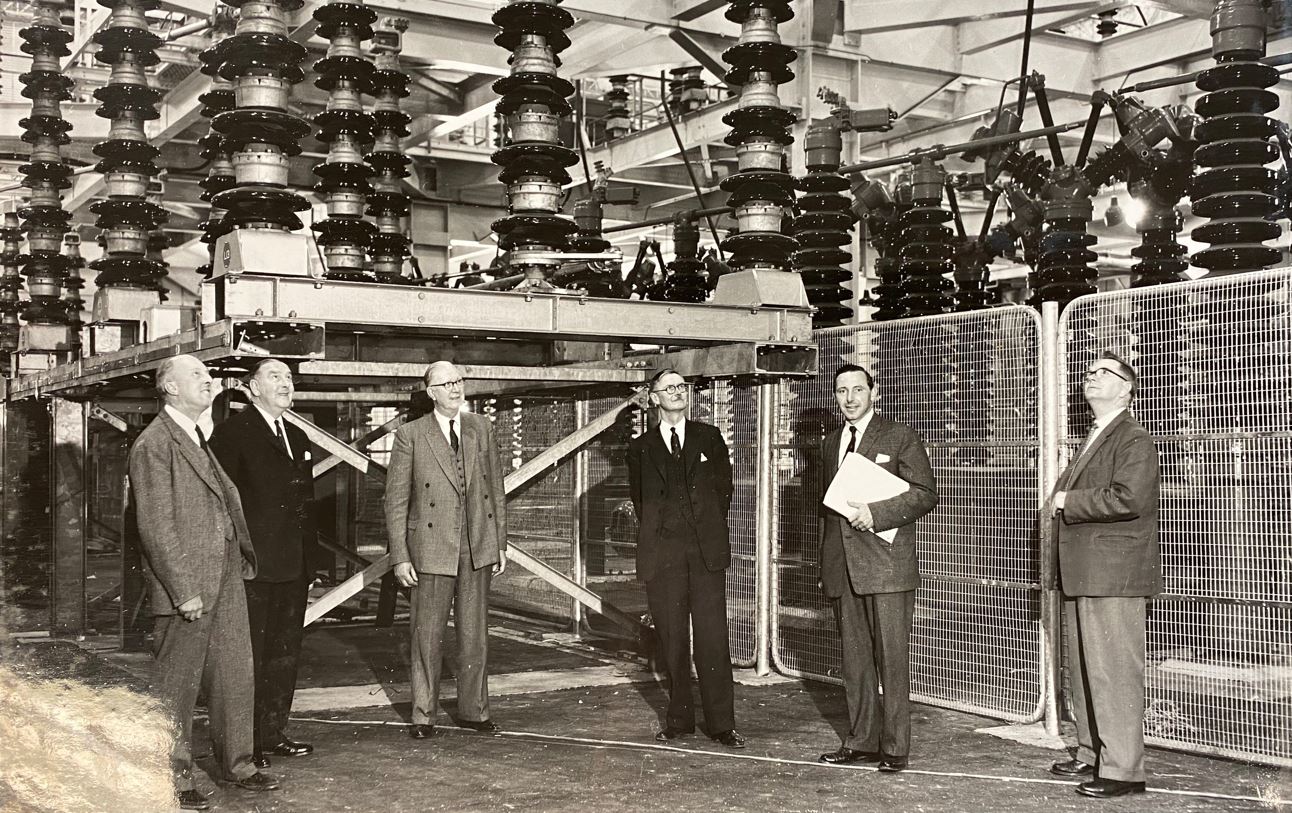

The 275kV supergrid was energised 70 years ago, ushering in a new energy era in Britain. Discover some of the major transmission network investments that have evolved and adapted the grid since to power our changing nation.

A lasting legacy

The original 275kV supergrid was engineered during the fifties to easily accept future upgrades. As technology advanced, switchgear was quickly replaced with higher rated equipment, tower designs evolved, and even bigger capacity lines were installed.

Early engineering innovation laid the foundation for one of the world’s cleanest, safest and most reliable transmission networks – and its evolution didn’t stop there.

An evolving network

The supergrid saw growth throughout the sixties and seventies, with new overhead lines, underground cables and substations connecting new sources of power like nuclear and gas plants.

In 1965 a 150 mile 400kV line was energised between Sundon substation in Bedfordshire and West Burton power station in Lincolnshire – the first of its kind in Britain, and another landmark moment in how we move power to where it’s needed.

Find out how we’re innovating at Sundon substation today to connect more clean power

As if to underline the success of the supergrid in connecting millions of people to power in new ways, the government launched a “Save it” campaign in the mid-seventies to encourage people to be more energy efficient.

National Grid takes the reins

The first half of the 20th century saw constant change in the energy industry. A series of bodies owned the grid and operated the power stations: the Central Electricity Board (CEB) from 1926; the British Electricity Authority (BEA) from 1948; and the Central Electricity Generating Board (CEGB) from 1958.

Learn more about the history of electricity in Britain

In 1990 the privatisation of the electricity industry transferred the CEGB’s transmission activities in England and Wales to the newly formed National Grid.

Our early colleagues set about continuing the growth of the transmission network. They inherited a grid with just over 200 275kV and 400kV substations; today that number has grown to over 330 as we’ve connected new generation and demand.

Dash for gas (and then wind)

Driving growth in the nineties was the ‘dash for gas’, which saw lots of gas plants connecting to the grid, including big power stations like Seabank in the south, and Killingholme and Connah’s Quay in Midlands and north.

More recently, our Killingholme and Connah’s Quay substations have connected clean energy to the grid. Upgrades at Connah’s Quay helped connect our network with renewable power in Scotland via our Western HVDC Link in 2019; and in 2022 we plugged the world’s biggest wind farm, Hornsea Two, into the grid at Killingholme.

The nineties also saw us kick off a project to build a 60 mile 400kV overhead line between Middlesborough and York, reinforcing the network in the region to manage increasing north-south power flows. In 1993, National Grid ESO’s Electricity National Control Centre (ENCC) opened in Wokingham, later replacing the seven regional control centres across Britain.

An olympic effort

The start of the 21st century saw some of the biggest and most complex transmission projects since the supergrid was built, many taking place in the capital.

A new substation built in 2003 on the site of our existing St John’s Wood facility laid the groundwork for a 12 mile cable under north London to transfer power to meet growing demand in the city.

Our engineers also jumped hurdles to help make the London 2012 Summer Olympics a success. Starting in 2005, we constructed two colossal tunnels to provide power to the games, using four huge tunnel boring machines.

The machines weren’t idle for long – the first phase of our £1 billion London Power Tunnels (LPT) project got underway in 2011, rewiring the capital to keep it connected to clean, secure power. The second phase of LPT is well underway, as part of which we’re building a UK-first SF6-free substation.

On the right track

Today’s network is playing a key role decarbonising transport in Britain. Connection of the main rail lines directly into our 400kV system has been ongoing since 2005 with the electrification of the West and East Coast Mainlines. It continues with our work on the Midland and Great Eastern Mainlines, and Core Valleys Lines in Wales.

Last year we also connected the Oxford Energy Superhub to the grid, which is delivering electricity to 42 public rapid EV chargers, with a connection point also ready at Oxford Bus Company.

Connecting continents

In 1952, a year before he switched on the supergrid at Staythorpe, BEA chairman Sir John Hacking told an energy conference that he saw “the possibility of interconnection with the continent on the horizon”.

His vision became a reality in 1961 when the first cross channel HVDC cable was commissioned between England and France, operating until 1980.

The first high capacity interconnector between the two countries, IFA-1, followed in 1986. Interconnection of our transmission network beyond our shores is ongoing, with each link boosting system security and resilience: we’ve connected six further subsea cables with the Netherlands (2011), Ireland (2012), Belgium (2019), Norway (2021) and two more with France, with more (including with Germany and Morocco) planned before 2030.

Our grid today

The original supergrid is a story of remarkable engineering prowess and transition – and it’s one that continues today. We’re investing billions to innovate and evolve the transmission network, including through The Great Grid Upgrade – the biggest overhaul of our electricity grid in generations.

Where the early supergrid was built around the power plants of the Midlands, tomorrow’s network will take a different shape, connecting us to clean energy out at sea – meaning new infrastructure, in new places. Today, new technology and innovation is already driving that clean energy transition. From our new T-pylons which are bringing low carbon electricity to millions, to new interconnectors such as Viking Link to exchange renewable power with our neighbours, we’re building the next supergrid to help Britain reach net zero.